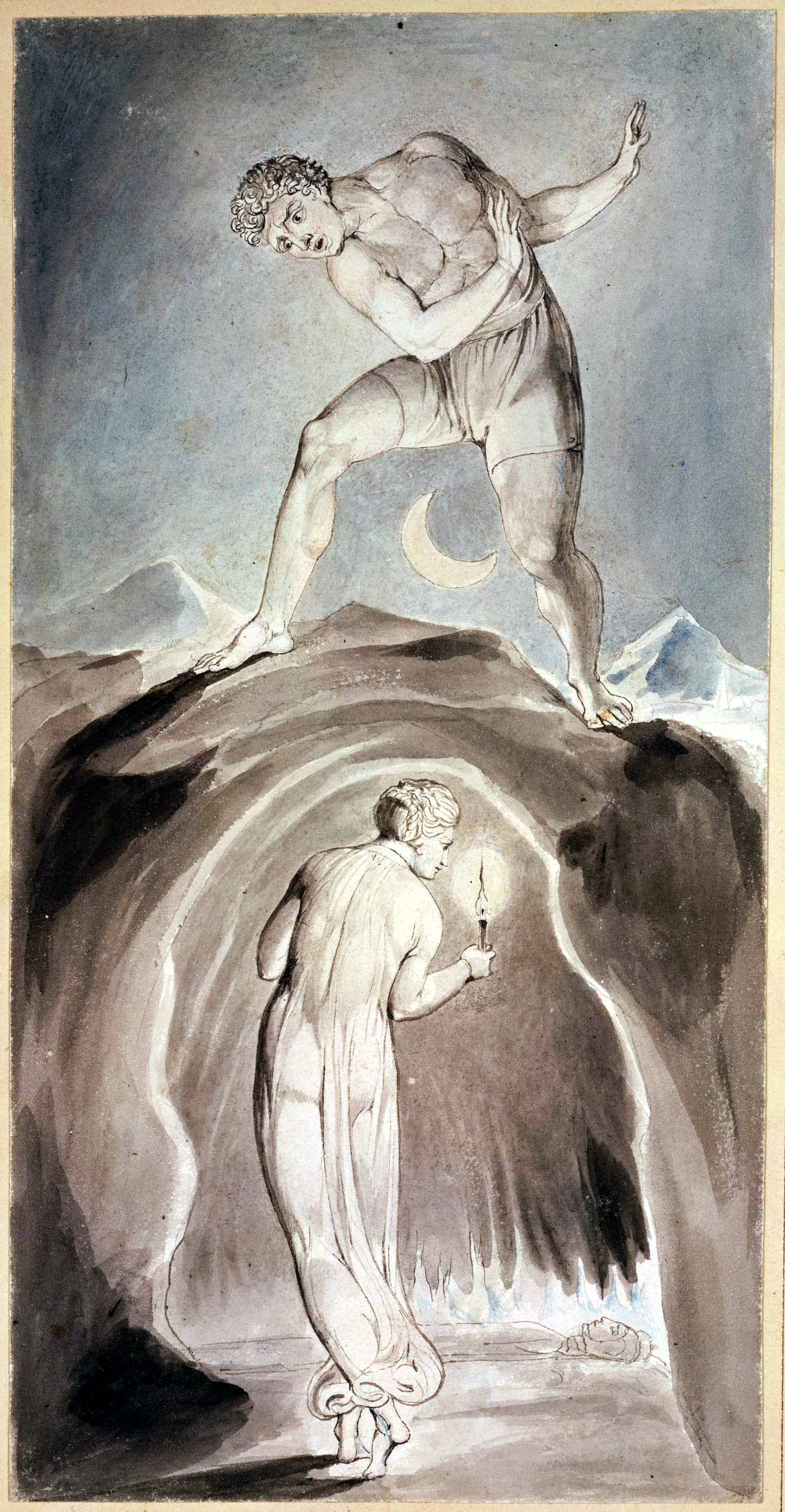

‘Who slept among the heroes of Sardinia’ — Aristotle on time and memory

“But surely, we recognize time whenever, marking by the before and after, we marked a change. And that’s when we say time has passed: when we have grasped in the change a perception of the before and after. We mark them by grasping that one thing is different from another, and a certain interval is different from them. For when we consider the extremes to be different, and the soul says that there are two nows—the one before, the other after—then this we also assert to be time. For what is marked by the now is thought to be time. Let us assume this.”

ἀλλὰ μὴν καὶ τὸν χρόνον γε γνωρίζομεν ὅταν ὁρίσωμεν τὴν κίνησιν, τῷ πρότερον καὶ ὕστερον ὁρίζοντες· καὶ τότε φαμὲν γεγονέναι χρόνον, ὅταν τοῦ προτέρου καὶ ὑστέρου ἐν τῇ κινήσει αἴσθησιν λάβωμεν. ὁρίζομεν δὲ τῷ ἄλλο καὶ ἄλλο ὑπολαβεῖν αὐτά, καὶ μεταξύ τι αὐτῶν ἕτερον· ὅταν γὰρ ἕτερα τὰ ἄκρα τοῦ μέσου νοήσωμεν, καὶ δύο εἴπῃ ἡ ψυχὴ τὰ νῦν, τὸ μὲν πρότερον τὸ δ' ὕστερον, τότε καὶ τοῦτό φαμεν εἶναι χρόνον· τὸ γὰρ ὁριζόμενον τῷ νῦν χρόνος εἶναι δοκεῖ· καὶ ὑποκείσθω.

Aristotle, Physics 4.11, 219a22-30

“Memory is neither a perception nor a conception; instead, it is a state or affection of a certain one of them, when time has passed. There is no memory of the now in the now, as we said; rather, perception is of the present, hope of the future, memory of the past. For this reason, all memory follows time. Thus, only those animals which perceive time can remember, and with that by which they perceive.”

ἔστι μὲν οὖν ἡ μνήμη οὔτε αἴσθησις οὔτε ὑπόληψις, ἀλλὰ τούτων τινὸς ἕξις ἢ πάθος, ὅταν γένηται χρόνος. τοῦ δὲ νῦν ἐν τῷ νῦν οὐκ ἔστι μνήμη, καθάπερ εἴρηται [καὶ πρότερον], ἀλλὰ τοῦ μὲν παρόντος αἴσθησις, τοῦ δὲ μέλλοντος ἐλπίς, τοῦ δὲ γενομένου μνήμη· διὸ μετὰ χρόνου πᾶσα μνήμη. ὥσθ' ὅσα χρόνου αἰσθάνεται, ταῦτα μόνα τῶν ζῴων μνημονεύει, καὶ τούτῳ ᾧ αἰσθάνεται.*

Aristotle, On Memory 1, 449b24-30

*note: Aristotle thinks time is something that happens to us, that affects us, like color or taste or touch.

“Neither (is there time) without change: for when we ourselves do not change our state of mind, or when we have not noticed ourselves changing, then time does not seem to us to have passed—just like it does not for those whom the stories tell slept among the Heroes in Sardinia: when they wake up,* they connect the earlier now with the later now and make them one, cutting out the interval. So, just as if the now were not different but one and the same, there would not be time, so, too, when we do not notice a difference, it does not seem that there has been an interval of time.”

Ἀλλὰ μὴν οὐδ' ἄνευ γε μεταβολῆς· ὅταν γὰρ μηδὲν αὐτοὶ μεταβάλλωμεν τὴν διάνοιαν ἢ λάθωμεν μεταβάλλοντες, οὐ δοκεῖ ἡμῖν γεγονέναι χρόνος, καθάπερ οὐδὲ τοῖς ἐν Σαρδοῖ μυθολογουμένοις καθεύδειν παρὰ τοῖς ἥρωσιν, ὅταν ἐγερθῶσι· συνάπτουσι γὰρ τῷ πρότερον νῦν τὸ ὕστερον νῦν καὶ ἓν ποιοῦσιν, ἐξαιροῦντες διὰ τὴν ἀναισθησίαν τὸ μεταξύ.* ὥσπερ οὖν εἰ μὴ ἦν ἕτερον τὸ νῦν ἀλλὰ ταὐτὸ καὶ ἕν, οὐκ ἂν ἦν χρόνος, οὕτως καὶ ἐπεὶ λανθάνει ἕτερον ὄν, οὐ δοκεῖ εἶναι τὸ μεταξὺ χρόνος.

Aristotle, Physics 4.11, 218b21-29

*Two versions of the story are told by Ross in his commentary (and what follows is roughly a quotation from him, p. 597). Philoponus says sick people went to the heroes of Sardinia for treatment, slept for five days, which they didn’t remember when they woke up. Simplicius says that nine children born to Heracles died in Sardinia, did not decay, and looked like men asleep. Rohde (Rhein Mus. 35 (1880), pp. 157-163) points out the story’s affinities to legends which represent Alexander the Great, Nero, Charlemagne, Arthur, and Barbarossa as sleeping in the earth until they awake and come to revisit their people.