Endings

“Zeus, god of the gods, who rules with force of law, was able to see these things clearly. When he realized that good people were reduced to struggling, he wanted to grant them justice so that they might take control of themselves and return to harmony. He assembled all the gods together into their most honoured home, which, set at the centre of the entire cosmos, looks down upon all who share in creation, and once he had assembled them, he said:”*

θεὸς δὲ ὁ θεῶν Ζεὺς ἐν νόμοις βασιλεύων, ἅτε δυνάμενος καθορᾶν τὰ τοιαῦτα, ἐννοήσας γένος ἐπιεικὲς ἀθλίως διατιθέμενον, δίκην αὐτοῖς ἐπιθεῖναι βουληθείς, ἵνα γένοιντο ἐμμελέστεροι σωφρονισθέντες, συνήγειρεν θεοὺς πάντας εἰς τὴν τιμιωτάτην αὐτῶν οἴκησιν, ἣ δὴ κατὰ μέσον παντὸς τοῦ κόσμου βεβηκυῖα καθορᾷ πάντα ὅσα γενέσεως μετείληφεν, καὶ συναγείρας εἶπεν:

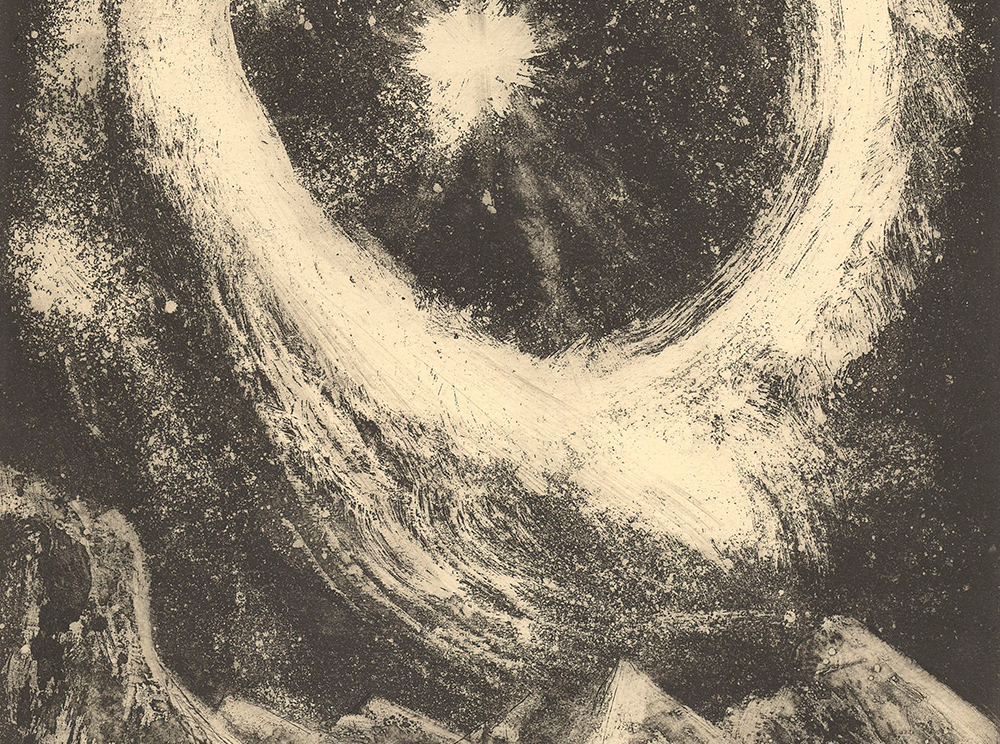

*To the right is the last column of the Critias, written on parchment in one of the oldest manuscripts of Plato we have, Parisinus gr. 187 f. 151r. This manuscript is at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, and it’s been been dated to around 850-875 CE.

The Critias ends mid-sentence. The Atlantans’ story is never resolved. Maybe Plato died before he finished it, maybe he couldn’t think of what Zeus was supposed to say. To mark this the copyist writes the εἶπεν (“he said”) with a colon in the centre of the last line—two dots bordering on universes of possibilities.